Year:

Applicant:

Institution:

Email:

phillip@queensu.ca

Project ID:

170309

Approved Project Status:

Project Summary

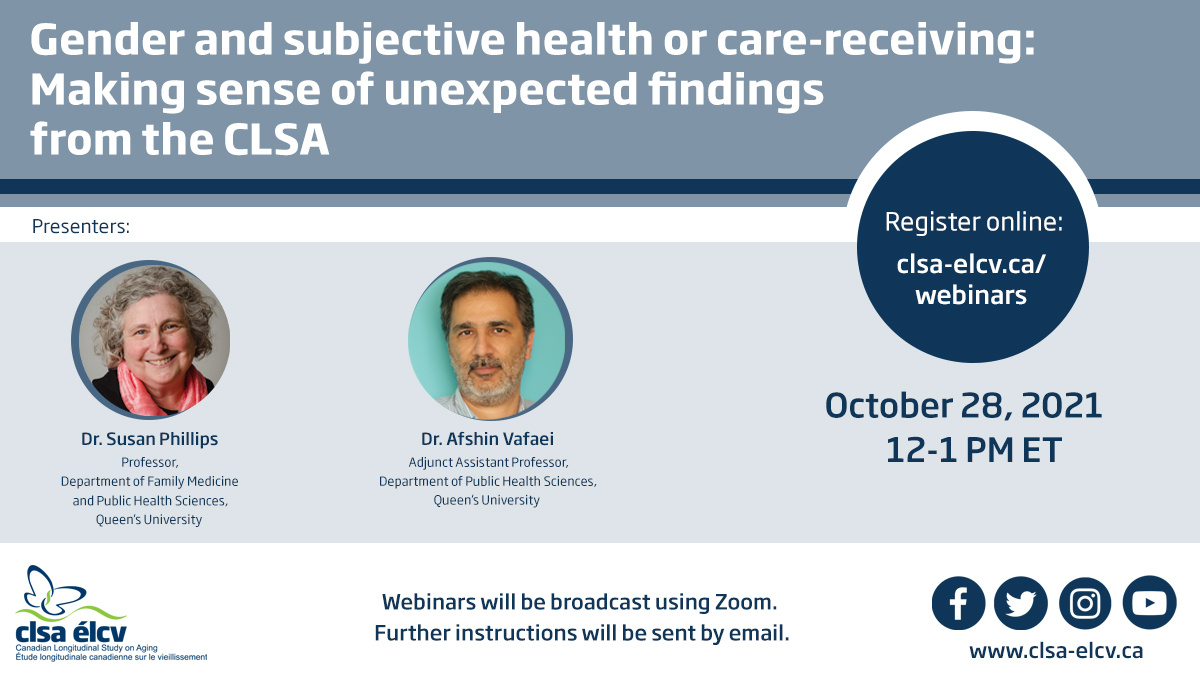

Self-rated health (SRH) is a widely-used indicator in clinical assessments and research to assess overall health. SRH can be evaluated using a five-item question, asking respondents to rate their health on a scale from poor to excellent. It allows respondents to weigh all aspects of health, subjective and physical, against their own personal definition of health. The validity of using SRH as a measurement of health is supported by the well-established association between SRH and mortality. Predictors of SRH have also been identified, including physical, mental, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors. The idea is that these predictors can be targeted to improve SRH, ultimately to improve overall health. However, whether these predictors are the same for women and men is unclear. Thus, the purpose of this study is to understand gender differences in predictors of SRH.

Project Findings

We examined: 1) associations between gender and self-rated health; and 2) whether state-funded medical and support services for care in the home correct for individual and social inequities in access to home-care use among older Canadian adults. Women in the CLSA dataset have higher self-rated health than men. This apparent health benefit for women is, however, nuanced. When intersections of sex and wealth and other social locations are considered the gender differential diminishes. Diminished physical function was most strongly aligned with formal care use, while age, living arrangement, having no partner, depression, self-rated health and chronic medical conditions played a lesser role in the care pathway. Notably, sex/gender, were not determinants. Characteristics aligned with informal care were first—need, then country of birth and years since immigration. Although often considered marginalized, women, immigrants, or those of lower socioeconomic status utilized formal care equitably. Formal care was also differentially available to those without the financial or human resources to receive informal care. Need, primarily medical but also arising from living arrangement, rather than socioeconomic status or gender-predicted formal care, indicated that universal government-funded services may rebalance social and individual inequities in formal care use.